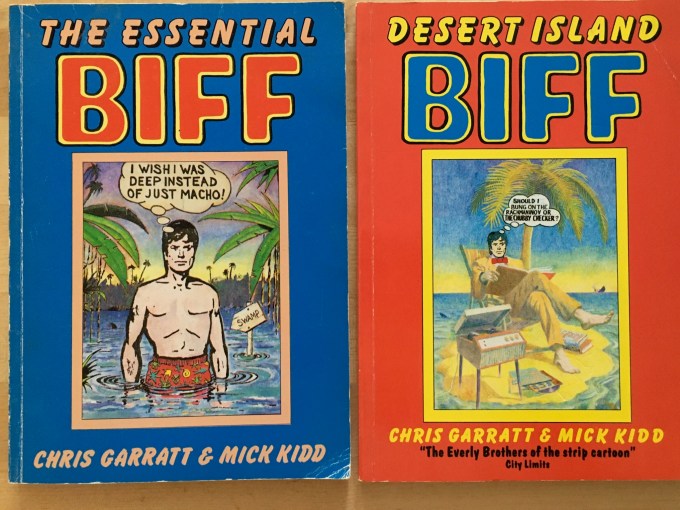

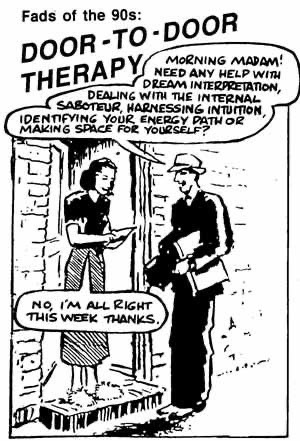

Biff is a British cartoon strip created by Chris Garrett and Mick Kidd in the 1980s. Its humour deflates pretentiousness by placing it in an everyday setting. Melodramatic, self-regarding, would-be poets are brought down to earth by ordinary people. Or pompous language is deflated by a non-sequitur

The cartoons are funny but they have a ring of truth. When I read them I know I’m laughing at myself. Oscar Wilde would have appreciated them. He tells a story of once going down to the Seine and, in true Romantic poet style, thinking of jumping in. On a bridge he saw another man looking down into the river. “Are you also a candidate for suicide?” Wilde asked. “No, I’m a hairdresser” came the reply. The comical non- sequitur so cheered Wilde up that he changed his mind.

In one cartoon a 1950s style teenager despairs with the words “I feel like a lost sock in the laundromat of oblivion”. With my slight adjustment to the boys name his girlfriend asks “Is it Angst, Oscar. Or is it just the lager?”