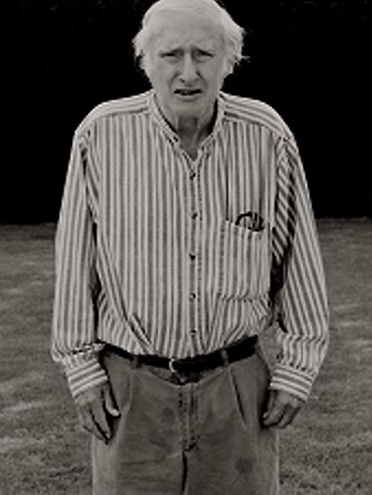

Andrew Loog Oldham

Oldham with the Stones

Pierre-Francois Palloy

Palloy’s model of the Bastille

Hype and popular music go hand in hand. The Rolling Stones would probably have made the big time without their manager Andrew Loog Oldham, but his creative use of media manipulation certainly helped. Having previously worked for Brian Epstein and the Beatles he had seen how money could be made by moulding and promoting a band. He didn’t hang about. The moulding stage came first. He sacked their piano player Ian Stewart because his looks did not match the image about to be created. He changed the musical direction of the band by encouraging Mick Jagger and Keith Richards to write pop/rock songs to replace the blues covers they were used to performing, at a stroke pushing the Blues purist Brian Jones down the pecking order. Promotion came next. Oldham successfully hyped up the Stones’ “bad boy” image and generated widely quoted headlines such as “Would you let your daughter go with a Rolling Stone?” The press lapped it up. His provocative cover notes on their second album encouraged fans to mug a blind beggar for funds to buy the album. Outrage. The Stones never looked back. Andrew Loog Oldham was 19 years old.

Pierre-François Palloy was an 18th century chancer, always on the lookout for the next big deal. In July 1789, in Paris, there was no bigger deal than the recently ransacked prison the Bastille. So Palloy acquired it, or at least the rights to demolish it and dispose of the debris. He had a grander plan than that, however. He would sell the stones of the Bastille, but more importantly he would sell an idea of the Bastille, an idea that lasts to this day. It was people like Palloy who turned the Bastille into a national symbol of liberated humanity. Others did it for political gain; Palloy did it to increase the value of his stones. Loog Oldham would have been proud. He did the same.

Palloy promoted the cult of the Bastille as a political tourist attraction with guided tours, historical lectures and accounts which hugely exaggerated the horrors of its dungeons, the numbers of its persecuted prisoners and the suffering they had endured. The truth was somewhat different. No 18th century jail was pleasurable, of course, but the Bastille was by no means the worst. Its most famous inmate was the Marquis de Sade. He had a desk, a wardrobe for his dressing gowns and silk breeches, four family portraits, tapestries on his walls, velvet cushions and pillows, mattresses, eau-de-cologne fragrances, and night lamps to help him get through his personal library of 133 books. He moved out a week before the Bastille was stormed. 7 prisoners were found inside, four of them forgers, one an aristocrat, plus two lunatics. No persecuted, tortured victims of the state. Media hype told otherwise. Prints began to emerge in which bits of armour were revealed as fiendish “iron corsets”, and a printing press as a wheel of torture. Palloy Enterprises capitalised on and furthered such fake news. By November 1789 he had completed the demolition of the prison and the reconstruction of its new image was well underway. So Palloy began to sell his product. Out of the stones of the Bastille he had miniature working models made of the prison and 246 chests of souvenirs which he took on the road, touring the French provinces. The chests were full of stone paperweights shaped like small Bastilles, snuffboxes and daggers. So familiar. Both Oldham and Palloy followed the same plan. Find your product, dismantle it, recreate it, invest it with a “bad boy” image, then take it on tour.

Hype did not appear fully-formed in the 20th century. It has a long history. With our modern know-how we like to think of ourselves as superior to previous generations but, let’s face it, there was not much Andrew Loog Oldham could teach Pierre-François Palloy about selling the stones.