“A lovestruck Romeo sings a streetsuss serenade

Laying everybody low with a love song that he made” Mark Knopfler/Dire Straits Romeo and Juliet (Making Movies)

1963. I’m doing the Twist in the youth club. The music is coming from a record-player perched on a wooden chair placed on the stage of the school hall. The music stops mid-song and I look over towards the stage and see a lad brandishing an L.P. sleeve. He’s shouting “This is it!” He puts the first track on and I hear a count-in –

” 1, 2, 3, 4. Well she was just 17, You know what I mean”

The Beatles. First time we’d heard them. Pure energy. We stopped Twistin’ – and started jumpin’.

This was my Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom moment, as Nik Cohn might put it. He wrote a book with that title – quoting Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti – arguing that meaningless lyrics are all pop music needs, that Awopbopaloobop is worth more than any of Bob Dylan’s lyrics.

I understand the point he is making but I think he’s missing something. Pop music has two modes – a public one and a private one.In a crowd, at a concert, lyrics don’t always matter. I started going to football matches in 1963. I went with a dozen or so friends from school. This was in the days when you stood on the terraces, and to get a good spot on the halfway line we used to arrive one and a half hours before kick-off. We spent the 90 minutes singing along with the music coming over the P.A. The louder the better. Words of no importance.

On my own, however, reading the lyrics was part of the enjoyment. That was what an L.P. sleeve was for. I read books in an armchair in front of the fire, comics in the street walking home from the newsagents, and music lyrics on the bus back from town where I had just bought the L.P. So you began to put singers/groups into one of two mental boxes. Beatles/Stones – box labelled “lyrics not important”. Dylan/Paul Simon – box labelled “lyrics worth reading”

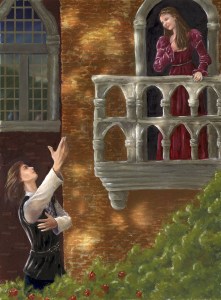

And this is where Mark Knopfler comes in. Category 2 – lyrics of interest. Take “Romeo and Juliet” from the L.P. “Making Movies”. Exhibit A in the case for the defence of the worth of pop lyrics. The scene it describes is both touching and funny. Romeo is a “lovestruck” teenager getting short shrift from his Juliet, a girlfriend with attitude. Both express themselves in hip, teenage slang. Romeo’s icebreaker eschews subtle fore-play – “You and me babe, how about it?” No swooning from Juliet – “You nearly gimme a heart attack …. anyway, what you gonna do about it?” Romeo pulls out the big guns with a bit of youthful, clichéd exaggeration “You exploded into my heart”, takes in the blank stare and fights back with “how can you look at me as if I was just one of your deals?“. There is a name for this style of writing. It has literary pedigree. It is called Skaz and it has its roots in Russian literature. It is recognisable to us, however, because it has flourished most successfully in American novels. Think “Huckleberry Finn”. Or even better, think “Catcher in the Rye”. Holden Caulfield is our Romeo with a large chip on his shoulder. Salinger’s novel is written in Skaz. Moreover, it would be nothing without it. Holden’s way of speaking holds our attention throughout. The story certainly doesn’t – nothing really happens. It is a wonderful “tour de force”, wholly dependent on the successful use of teenage Skaz. Holden’s frustration, like Romeo’s, is expressed in colloquial language – “jerk”, “big deal”, and most famously “phoney”. Exaggerations such as “that killed me” abound. You feel for Holden and Romeo because of their sad but funny inarticulate speech. “I can’t do the talk like they do on the T.V.” says Romeo, but, like Holden, he comes across as genuine. In effect, their language is a kind of guarantee of their genuineness. We feel they are speaking from the heart. It’s rough, not crafted or polished for effect. As Holden would say, their language is not that of the “phoney” world of adults. Knopfler reinforces this effect through his pastiche of the original “Romeo and Juliet”. The teenage Romeo may not speak like Shakespeare but his love is genuine. And he might add that if he spoke poetry it would be false emotion. Knopfler’s lyrics are also witty, in that he makes allusions to that other hip version of Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story. Knopfler’s two protagonists, like the Jets and the Sharks, have “Come up on different streets”. Romeo refers to his street gang in “All I do is keep the beat and bad company”. And it is easy to miss the reference to a famous line in the song “Somewhere” in “There’s a place for us you know the movie song”. Best of all, Knopfler manages to bring the two elements of his song – Skaz language and Shakespearean pastiche – together in one funny pun. Juliet remarks casually “oh Romeo, yeah you know I used to have a scene with him”.

I rest my case. I like “Ballroom Blitz” as much as anyone when I’ve lost it in a crowd. But, on the top deck of a bus, with half an hour to kill, give me the L.P. sleeve of “Making Movies”.

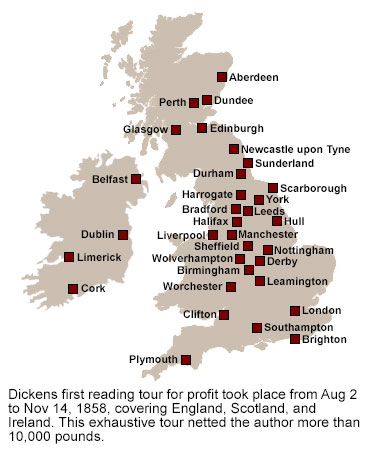

The tour had been long and exhausting. Audiences were huge and everywhere ecstatic. The artist performed his usual greatest hits and was mobbed in the street outside the theatre. Profits were enormous and ticket touts had a field day. The performer found sleep impossible after the usual adrenaline rush and took to using sedatives. Who’s this, you might ask. Frank Sinatra in the 1950s? Mick Jagger in the 60s? Actually, no. This is Charles Dickens on his American Tour in 1857.

The tour had been long and exhausting. Audiences were huge and everywhere ecstatic. The artist performed his usual greatest hits and was mobbed in the street outside the theatre. Profits were enormous and ticket touts had a field day. The performer found sleep impossible after the usual adrenaline rush and took to using sedatives. Who’s this, you might ask. Frank Sinatra in the 1950s? Mick Jagger in the 60s? Actually, no. This is Charles Dickens on his American Tour in 1857.